The Pro’s and Con’s of Using Pre-Existing Logic/Templates in Root Cause Analyses (RCA)

There has been an ongoing debate for decades as to whether the use of pre-existing logic for conducting Root Cause Analyses (i.e. RCA templates and/or libraries) – helps or hinders the analysis results. Does the use of such pre-existing logic expand the thinking of the team members or does it lead the team to pre-determined conclusions, and away from other conclusions not considered in the pre-existing logic made available? We will explore the fine line between these opposing views and see if there is a middle ground for consensus.

Root Cause Analysis/Methodology

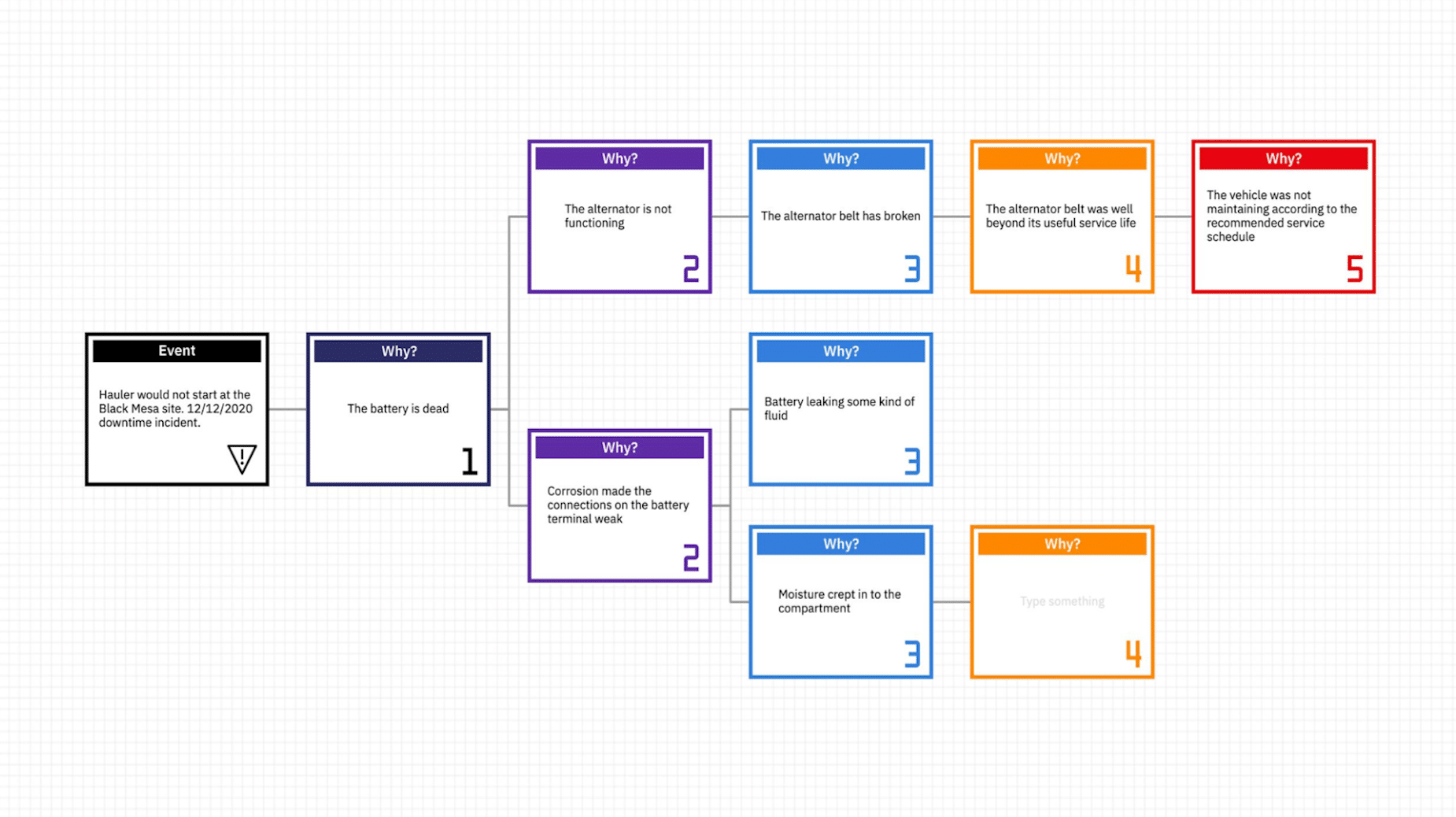

This article’s intent is not to debate the definition of “root cause analysis”, because if it did, it would go on indefinitely! For those readers who have participated in such discussions on various online RCA forums, you know what I mean. However, I think we can most all agree that no matter how you define RCA, that undesirable outcomes are the result of multiple cause-and-effect relationships that line up over time. No matter what tool you use to express these cause-and-effect relationships (i.e. – logic tree, fault tree, why tree, causal factors tree, factor tree, fishbone diagram, 5-Whys, etc.), we nonetheless can agree that these relationships must exist for the undesirable outcome to surface.

With a lack of a standardized definition of RCA comes the ambiguity of terms related to RCA itself. What is a Root Cause? Again, the answer to this question suffers the same fate in the public domain as Root Cause Analysis and is not the focal point of this article.

Let’s begin with the concept that flawed systems oftentimes adversely impact human decision-making. Flawed systems are the organizational/management systems we use to help us make better decisions. Such systems include, but are not limited to, our training, human resources, purchasing practices, procedures, policies, IT, regulatory, etc.

For example, I may have decided to use too much lubricant for a pump in my area causing it to fail prematurely. The basis of my decision is that I am an operator who has recently been given the additional task of lubricating equipment that I operate. This additional responsibility comes as budgets are cut and when mechanics retire, the company is not replacing them. These responsibilities are shifted to operations without training operators in proper lubrication practices.

In this scenario, we have the following:

Figure 1 – The “Root” System

The point we are trying to get across (Figure 1) is not the comprehensiveness of the example at each level, but a simple understanding of how our systems affect our decision-making and consequently cause a physical (observable) effect to emerge. It does not matter if the RCA approach you use labels causes differently (i.e. – approximate causes, near root causes, if they represent the cause-and-effect relationships in the manner represented above.

As far as RCA goes, the above was a summary of methodology to gain a consensus on how failure occurs in a sequential series of parallel paths, converging at some point to cause an undesirable outcome (the Event). Now let’s move on to the role of pre-existing logic in RCA. The term ‘pre-existing logic’ will be used synonymously with ‘templates’ for the remainder of this blog.

RCA Libraries/Templates (Content)

Whereas before we were discussing methodology, now we will move to focus on content. An RCA process is essentially a framework of cause-and-effect relationships built around a set of methodology rules. This framework however has no content in the beginning. The burden falls upon the lead analysts and their team to develop hypotheses and validate whether they are true or not. This knowledge from the team members will be extracted, based on their respective experience in the field.

The greatest learning that will come from any successful RCA effort will be the learning that takes place during team meetings. By having to continually ask how something could happen, we must explore in our own minds as to how it could happen from a cause-and-effect standpoint. For instance, if it is found that a bearing has failed, the ensuing question would be, “How could a bearing fail?” Now most maintenance people and engineers have been around bearings for their entire careers. They know them inside and out and replace them daily. This seems like a very easy question and your likely answers would include things like:

- Misalignment

- Improper installation

- Wrong bearing

- Defective bearing

- Over-lubricated

- Under-lubricated

- Wrong lubricant

There are many more potential paths to failure, but you get the idea. When dealing with RCA we teach people to view the vertical cause-and-effect tree as a quasi-timeline. If we know a bearing has failed, can we imagine and visualize this in our minds and move back a small increment in time, to see what could have just happened to cause that bearing in order to make it fail? Most would not disagree that when looking at it this way, there are only four (4) plausible ways in which a bearing can fail (Figure 2):

Figure 2 – The Cause-And-Effect Relationships

Figure 2 – The Cause-And-Effect Relationships

Any of the other possibilities listed earlier, would eventually cause one or more of the above failure mechanisms to surface on the bearing. So if it was proven that “fatigue” was the culprit in this case and there was no evidence of the other failure patterns, we would mark the others as not true and continue following “fatigue” down the tree (Figure 3). The next natural question would then be, “How could we have had fatigue of the bearing?” And the questioning goes on the same.

Figure 3 – True vs. Not True Based on Sound Evidence

By extracting this knowledge from the team members, we are constructing a knowledge or experience tree. The team members are learning because their minds are being exercised as to which hypothesis is the cause, and which is the effect. It is not always as simple as we would like it to be but having to think through it is definitely the greatest learning opportunity. In this manner we can derive the logic in our minds and retain it for future use.

In the end, when the analysis is complete and recommendations are implemented, we will eventually be able to measure the effectiveness of our analysis by its impact on the bottom-line. Something had to get better like a reduction in injuries, increased production, decreased cost or frequency, improved customer relations, etc.

If we have a successful RCA now, based on the knowledge and experience of our team members, how can we leverage that logic for the benefit of the corporation?

Corporate Memory/Leveraging Knowledge and Experience

Many of us (although the number is dwindling ) can remember the “re-engineering” era of the late 80’s and early 90’s. Unfortunately, re-engineering became associated with census reduction and efficiency measures. This certainly was the era of the golden handshake where people were incentivized to accept early retirement packages so that the census could be reduced. This seems logical in concept but was very poorly applied in application.

Corporations started to indiscriminately offer these retirement packages hoping that a certain number of people would take them. I remember one Fortune 100 company at the time that estimated 6,000 people would take the early retirement package and 12,000 actually did! Imagine the chaos this caused in that company, as many of the new retirees were now hired back as contractors at greater rates, just to keep production rolling!

Think about who tended to take these early retirement packages? Those that knew they could get a healthy severance and another job quickly are the ones that bailed. In other words, those with the most experience are the ones that left first! When you have a mass exodus of talent in a corporation, what danger does that pose? The danger posed is the loss of “corporate memory”. The knowledge and experience of the best problem solvers just left the corporation and took their internal laptops (their brains) with them. Therefore, all those people that knew how to solve the specific problems of their workplace are gone and the problems are now the responsibility of those left behind. This scenario was, and is, real today and represents a significant safety risk to the corporation and millions of dollars in potential production losses and unnecessary costs. As the Baby Boomers exit the workforce, this will be a growing problem, just like the lack of skilled trades in the workforce, to replace them!!

How can we combat against this real-world scenario? We can do so by capturing the successful logic of expert problem solvers using our RCA methodologies and tools described earlier. This is rarely done and when it is attempted, the way the logic is collected is inconsistent with the methodology and tools being applied.

Reliability Center, Inc. (RCI) has been aggregating, developing, and formatting such logic over the years. The result is an RCA library of successful logic which we will now call the PROACT® RCA Knowledge Management Template Libraries. We will use the terms ‘templates’ and ‘libraries’ synonymously in this blog. These thousands of cause-and-effect relationships have been developed using the logic of expert analyses in the field. They represent the actual logic used to solve mechanical, electrical, process, quality, safety, and human performance failures over the past 3+ decades.

These template libraries are structured in such a fashion that they can only be used with the search and navigational tools used in our PROACT® & EasyRCA solutions, as well as our partner’s product, PROACT® for GE APM®.

Imagine being on an RCA team meeting and getting stuck on a hypothesis, where you have exhausted the team’s experience, and seek to see what other’s might have suggested when they faced a similar situation in a prior analysis. Imagine doing this real-time and using Artificial Intelligence (AI) algorithms to call upon the logic used by others at that point in the logic tree. Think of the efficiencies that this brings to the table to expedite the analysis while making it more comprehensive and accurate.

For the purposes of this blog, I will continue to use screenshots from our EasyRCA solution. In Figure 4, Fatigue is entered as a hypothesis. The arrow is pointing to the tool bar to indicate that the brain icon is lit up orange. This indicates to the analyst that suggestions are available as to how fatigue can occur. By clicking on the brain icon, the panel of options opens on the left side. At this time, the team can review the ideas and determine which may be applicable to their case.

By selecting the options the team wants to include, they are automatically added to the tree. In this instance we picked ‘High Vibration’. The parent node as well as four (4) child nodes are added to the tree as expressed in Figure 5.

Figure 4– Key Word(s) Searching Within an Analysis

Figure 5 – Importing External Logic into Your Analysis

Figure 5 – Importing External Logic into Your Analysis

The Potential Pitfalls of Using Logic Libraries/Templates

As stated earlier, the greatest learning that can occur from RCA is from the questioning process that goes on during a team meeting. The constant striving or effort to understand the order in which factors occur, cause-and-effect (including parallel paths at the same time), is the critical learning point in the analysis. Templates, when not properly used, can reduce the effectiveness of this learning opportunity.

The key to optimizing the value of the templates is to use them as supplemental knowledge to that of the team members. If the templates are used as the primary knowledge to the analysis, then there is a potential for the learning process to be expensed. I call this potential situation “doing RCA like paint-by-the-numbers”. This is when the templates are used as a picklist of options and the intent is to quickly finish “a” logic tree quickly that on the surface will impress the people we present it to. It does not mean it is right, it just looks good.

Most of the time analysts would be tempted to use this picklist approach when they are under time pressure (and aren’t most of us under time pressure?…hence the real temptation). Anytime we are under time pressure to do anything, we will seek a way to take shortcuts. In RCA, those shortcuts come in the form of qualification, verification and validation (QV&V) of our hypotheses. If our goal is to complete an analysis quickly, we will rush to construct a logic tree and chances are not properly prove our hypotheses are correct, using satisfactory verification methods. When faced with either having a metallurgist look at a failed part or taking the opinion of a mechanic who has not been trained in metallurgy, we may opt to go with the path of least resistance and take hearsay over science to get the RCA done!

No RCA provider can regulate the way their RCA methodology will be applied; the best we can do is recommend proper practices for success. In the end, the responsibility of doing what is right falls on the lead analysts and their teams.

This is how RCI believes previous knowledge and experience should properly be used within an RCA process.

RCA Templates are No Panacea

When treating templates as supplemental knowledge to an investigation we should always be cognizant that all the possibilities will never be included in whatever listing we produce. What is listed is just past experience, what people have encountered before in similar situations. This does not mean there are no other possibilities that exist. We all come from unique working environments with unique variables at play (i.e. – processes, procedures, regulatory environments, cultures, etc.) Templates should NOT be viewed as all-inclusive and we should continually press the boundaries of our team’s experience for looking at unique possibilities that could have occurred, always building on our template database and creating more comprehensive templates as a result. Such knowledge bases should always be organically growing based on the diversity of knowledge continually input into the system.

About the Author

Robert (Bob) J. Latino is former CEO of Reliability Center, Inc. a company that helps teams and companies do RCAs with excellence. Bob has been facilitating RCA and FMEA analyses with his clientele around the world for over 35 years and has taught over 10,000 students in the PROACT® methodology.

Bob is co-author of numerous articles and has led seminars and workshops on FMEA, Opportunity Analysis and RCA, as well as co-designer of the award winning PROACT® Investigation Management Software solution. He has authored or co-authored six (6) books related to RCA and Reliability in both manufacturing and in healthcare and is a frequent speaker on the topic at domestic and international trade conferences.

Bob has applied the PROACT® methodology to a diverse set of problems and industries, including a published paper in the field of Counter Terrorism entitled, “The Application of PROACT® RCA to Terrorism/Counter Terrorism Related Events.”

Recent Posts

How to Improve Your RCA Program: A Practical Guide for Reliability Leaders

The 2026 Reliability Cost Curve: How World-Class Teams Bend It Downward

The Reliability Leader’s 2026 RCA Playbook: A Straightforward Guide to Starting the Year Strong

Why You Never Have Time for Root Cause Analysis (And How World-Class Teams Fix It)

Root Cause Analysis Software

Our RCA software mobilizes your team to complete standardized RCA’s while giving you the enterprise-wide data you need to increase asset performance and keep your team safe.

Root Cause Analysis Training